Today we go into a playful and a bit provocative interpretation of our beloved Disney animated movies: if the beautiful and flawless princesses and protagonists of these stories (delivered to our imagination in the simplified yet exciting Disney version) suffered from a psychopathological disorder, which could it be?

We imagine a sort of clinic history for five female characters:

- Cinderella

- Aurora (Sleeping Beauty)

- Ariel (The Little Mermaid)

- Belle (Beauty and the Beast)

- Alice in Wonderland

Cinderella is a thoroughly good girl, submissive and very prone to sacrifice: she never escaped the cruel exploitation imposed by her stepmother and stepsisters. Her attitude to serve and to put others and their needs above her own remembers the masochistic personality type (also called “self-defeating”), identified by psycho-diagnostic manual PDM (Psychodynamic Diagnostic Manual, 2006). This profile concerns individuals who can not help but find themselves in conditions of suffering. According to common sense, the masochist is one who “enjoys suffering.” Actually, it is not about enjoyment: it concerns individuals who have been used or forced to fill the role of the suffering person because of their emotional stories and, most of the times, they have been accepted only by virtue of that. Or, even, they have been accustomed to think that suffering is the only way to deserve love or consideration. The PDM identifies two subtypes: the moral masochist and the relational masochist. The former nourishes the implicit belief that their suffering demonstrates a moral superiority over others. The latter is characterized by the pathogenic belief that maintaining important relationships is possible only if they suffer, and that if they stopped no one would be willing to care for them.

Aurora (“Sleeping beauty”)‘s diagnosis is immediate: did she suffer from hypersomnia? It is a very complex disorder and, inexplicably, public attention and awareness are very low. The Idiopathic hypersomnia (recognized by the international system of classification of diseases ICD 10, 1993) is a neurological and chronic sleep disorder characterized by excessive sleepiness. Currently there are no cures or treatments approved by the FDA (Food and Drug Administration). It stems from a problem in the brain systems that regulate sleep (probable dysfunction in midbrain-hypothalamic-limbic system) and manifests itself in episodes of prolonged sleep at night and not-REM sleep episodes throughout the day. There are organic differences compared to the better known Narcolepsy: the latter is characterized, besides from cataplexy (loss of muscle tone), by two or more periods of REM sleep within 15 minutes after falling asleep; in hypersomnia, however, less than two occur. The person suffering from hypersomnia also sleeps more than 10 hours a night, has trouble waking up even with the help of the alarm clock and feels confused and disoriented upon awakening (this is called “sleep drunkenness”). Sufferers can also exhibit sleep paralysis and hallucinations in the phase of falling asleep. Lastly, there may be excessive hunger (compulsive hyperphagia), hypersexuality and states of depression or manic excitement.

Ariel, the main character of “The Little Mermaid”, is a marine creature who does not accept her physical condition of mermaid and is unwilling to compromise. She could suffer from two obsessive disorders. The first is the Dysmorphophobia, which is in the “Obsessive Compulsive Disorder and Related Disorders” spectrum (DSM 5, APA 2013). Ariel’s extreme suffering for her physical condition remembers this disorder, characterized by persistent concerns about physical characteristics that, according to other people’s opinion, do not appear so excessive and uncommon (indeed, the presence of a tail must not seem so alarming in a world of mermaids and mermen!). It also involves repetitive behaviors and rituals (look in the mirror, touch the “defective part”), obsessive thoughts, stress, anxiety and mood decline. Typically, this disorder arises in a context that does not allow the consolidation of a good self-esteem: we think of Ariel authoritarian father, who is somewhat insensitive to her needs. The second is the compulsive hoarding disorder (DSM 5, APA 2013) or accumulation disorder, characterized by collecting goods – mostly useless – in unbelievable quantities and the inability to get rid of them. We remember Ariel’s crazy collection of unnecessary objects (especially in the abyss) recovered from the seabed: corkscrews, forks, candles, old glasses, coffee pots. People who suffer from this disorder feel a very strong attachment to each of these assets and fear they could not survive without them. They also feel a strong need to control them and therefore nobody is allowed to touch them or move them.

Belle, the heroine of “Beauty and the Beast”, is a young woman who, during her imprisonment imposed upon her by a monster, falls in love with him. This behavior is reminiscent of the Stockholm syndrome, describing the attachment and dependence of a victim towards her tormentor. The name was coined by psychologist Bejerot and refers to an episode that took place in Stockholm in 1973: a convict escaped from prison attempted a robbery at a bank and took three women and a man as hostages. When they were finally released, they developed a sense of appreciation and gratitude to the hostage-taker, who “had given them life.” It is not uncommon for hostages to say they had the opportunity to reflect on their lives and pledge themselves to change it if they had come out alive. Identification with the aggressor, a process likely involved in this syndrome, is a mechanism studied around 1930 by Ferenczi. The Hungarian psychoanalyst describes how the victim identifies with and introjects the threatening person, in order to cope with the anguish of a traumatic experience. Crushed by a helpless fear, the victims do not activate a rejection or defense reaction, instead they identify with what the attacker expects: they feel what the aggressor feels and try to anticipate his moves to survive. Anna Freud (1936) refers to it as a defense mechanism by which the victim can feel in the threatening role rather than threatened (which would be clearly more painful).

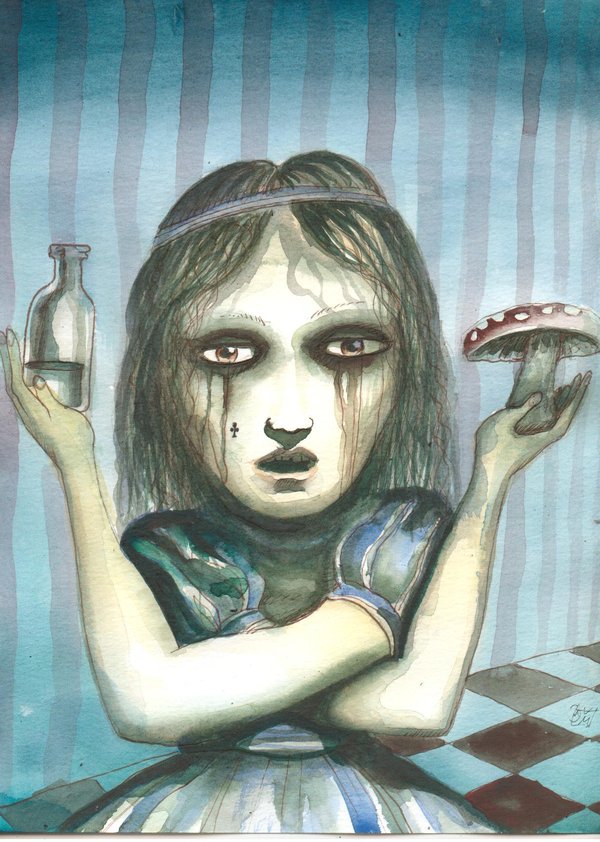

At last, we talk about Alice in Wonderland who, despite not being a proper princess, is still the protagonist of one of the most timeless Disney movies. Wanting to approach this masterpiece with a bit irreverent approach, we can imagine the sweet girl suffering from a psychotic disorder, specifically Schizoaffective Disorder (DSM 5, APA 2013). The Psychotic Disorders are characterized by a drastic loss of contact from reality. What if the long dream of Alice, populated by Cheshire Cat, Brucaliffo flowers and singing, was a hallucination? Schizoaffective Disorder is characterized by hallucinations (simple if they involve only one sensory channel, complex if they involve more), delusions (irrational and extremely solid convictions) and especially mood alterations. This can manifest itself in manic states (extremely high mood) and depression. It is not difficult to call to mind moments where the protagonist is incredibly enthusiastic and over-excited or, conversely, terribly discouraged and – literally – in a flood of tears.

In conclusion to this “Psychopathology of Disney princesses”, however, remember that, just like human complexity is difficult to summarize in diagnostic labels, the charm and the mystery of Disney heroines is certainly not explainable by classification systems. Nevertheless, thinking of these characters as subjected to psychological suffering could have an advantage: they feel truer, closest to us, less glossy and more real.

Psychologist, graduated in Clinical Psychology at Turin University

Info, contacts and articles here

Bibliography

America Psychiatric Association (2014). DSM 5, Manuale Diagnostico e Statistico dei disturbi mentali. Milano: Raffaello Cortina.

American Psychoanalytic Association (2007). PDM, Manuale diagnostico psicodinamico. Milano: Raffaello Cortina.

Ferenczi S. (1974). Confusione delle lingue tra adulti e bambini, in “Fondamenti di psicoanalisi, ulteriori contributi (1908-1933)”, vol. 3. Rimini: Guaraldi.

Ferenczi S. (2004). Diario clinico Gennaio-Ottobre 1932. Milano: Raffaello Cortina.

Freud A. (1937). The Ego and the Mechanisms of Defence. London: Hogarth Press and Institute of Psycho-Analysis.

Graham D.L., Rawlings E., Rimini N. (1988). Survivors of terror: battered women hostages, and the Stockholm syndrome. In: Feminist perspectives on wife abuse. Sage Publications.